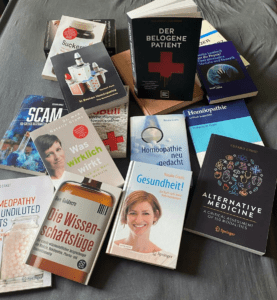

Prof. Lars Bräuer, together with the doctor and medical journalist Falk Stirkat, has just published the book “Der belogene Patient – Warum Impfkritiker, Wunderheiler und andere Scharlatane gefährlicher sind als jedes Virus” (The lied patient – Why vaccination critics, faith healers and other charlatans are more dangerous than any virus) . In it, the authors deal with the confusion of pseudo-medical, tradition-related and “personal experience” based medical errors and myths in a wide-ranging way. Of course, homeopathy as the “cornerstone” of the pseudomedical edifice also finds its due place in the book. Thankfully, we had the opportunity to exchange views with Prof. Bräuer.

INH: First of all, congratulations on the publication, Prof. Bräuer, and on the obviously broad reception. As the INH, we are of course particularly pleased that the researching and practising medical community is taking up the issue of pseudo-medical disinformation decidedly. We as INH have often complained that the dimension of this topic is not taken seriously (enough) by the professional side and that there is a lack of positioning from this side. What do you think might have been the reasons why the pseudo-medical promises were and are met with lassez-faire for so long – in science and politics? Has the serious impact on people’s health literacy really not been recognised?

Prof. Bräuer: Thank you very much for the congratulations and the opportunity to exchange ideas with you.

This is an interesting but also extremely complex question. The possible answers are certainly diverse and partly depend on the viewpoint of the observer. I think that the majority of scientists attach very little (actually none at all) importance to the topic of “pseudoscience” and in particular “pseudomedicine”. Serious research is enormously time-consuming, costs a lot of money and nerves and it is difficult to be successful in this competitive field. So why invest energy in magic and hocus-pocus. Pseudoscience therefore takes place below the radar of ‘real’ science, so to speak. I think many of my colleagues are not at all aware that there is a big and also serious problem here, which also costs human lives.

Another aspect here is certainly the inertia of the system. When I consider the bureaucratic and emotional hurdles that have to be overcome in order to make even small changes to the curriculum for students or even to adjust the licensing regulations for doctors or dentists, it is not surprising that one quickly runs out of steam here. Apart from a few faculties, homeopathy is still part of the medical curriculum – and no, I’m not talking about the subject of medical history here (where it should certainly belong) – I find that appalling. Fortunately, at least the Marburg Declaration has ensured that this is no longer examined by the IMPP (German Institute for Medical and Pharmaceutical Examination Questions). Nevertheless, it is suggested here that this branch of pseudoscience has a status, which it should not have. Every attentive student should actually cry out after the basic studies (where physics, chemistry and mathematics are taught) if a university lecturer suddenly violates all laws of nature with homeopathic nonsense. Well, and of course financial interests and lobbying should not be neglected in this discussion. In short, I think that people may already be aware of the effects on people’s health literacy, but due to the above-mentioned points they have no incentive or energy to change anything.

INH: Was there a specific impetus for you to take up the topic of deception through pseudo-medicine so broadly and effectively in terms of publicity? With her books, Dr. Natalie Grams has revived the public debate on homeopathy, which was thought to have been buried long ago – do you expect that there can now be a public discourse on the whole range of pseudo-medical nonsense on an even broader basis?

Prof. Bräuer: Yes, of course there was an impetus. Apart from the fact that I perhaps also like to provoke something, there are a lot of people in my circle of friends and acquaintances who are actually not aware that there is such a thing as pseudo-medicine at all – after all, you have a lot of trust in your treating doctor. I have been doing educational work here for many years, which is sometimes very tedious, because a lot of misinformation is deeply rooted in people’s opinions. I always find it particularly difficult to make it clear that facts have nothing to do with opinions.

Let’s stick to the example of homeopathy, which many people unfortunately still cannot differentiate from naturopathy or phytotherapy. In my experience, people here can be divided into three cohorts: those who know that homeopathy is simply rubbish; then those who don’t know but are unsure who or what to ‘believe’ (believe is such an incredibly unscientific word and should not really be used at all in this context); and of course those who sometimes even militantly advocate their fundamentalist views and are even willing to challenge long-standing friendships for their view. The latter, who from my experience are also often opponents of vaccination or supporters of conspiracy theories, we will certainly not be able to convince with our book, they will and would never read it anyway. But we will be able to reach those who are actually interested in information and facts.

I think Natalie Grams has contributed a great deal to the fact that the topic is once again in vogue – her own history and her presence in the social media certainly play a major role here. A “boring” university professor (like me) can easily be accused of simply not understanding the supposed principle of homeopathy, because he never – ex officio – got involved in it. Natalie Grams, on the other hand, who was once a convinced homeopath herself, has a completely different authenticity here. And that is very good!

Now, our book is not only about homeopathy, but also about other, as you call it, pseudo-medical nonsense – and of course it would be nice if we could stimulate a broad discourse. The current health policy situation certainly contributes to this.

INH: We have “specialised” in homeopathy, even though our family site covers a broader spectrum of pseudomedicine. Firstly, this is our expertise, and secondly, we see homeopathy and its false “public credibility” and apparent scientific mimicry as the “flagship” of pseudotherapies and remedies, which is not only completely out of place in the role of a medical method itself, but also paves the way for other nonsensical offers and a reliance on untenable promises. Would you assess homeopathy in a similar way?

Prof. Bräuer: I see it exactly the same way. Homeopathy is more or less the mother of all forms of pseudotherapy. It is a prime example of how medical regression can be made acceptable. And it is supported, promoted and protected by politics and the health system. This is actually shameful for a country that is known for its pioneers and scientific achievements.

INH: Health literacy is not just a buzzword, but a definite aim of health policy. According to recent studies, the general health literacy of the population is not at its best – homeopathy is a glaring example, but not the only one. In your opinion, does health policy at its various levels – from the ministry to the health insurance companies – simply do too little or even the wrong thing with regard to teaching health literacy? How can it be that in many cases it is left to private individuals or associations or consumer protection organisations to provide information about slippery slopes in health-related issues?

Prof. Bräuer: These are exactly the aspects our book deals with. I think many people are not at all aware that unscientific nonsense such as homeopathy is subsidised by a large number of health insurance companies, while unavoidable and prognostically useful preventive examinations (e.g. prostate cancer screening) are not paid for by the insurance companies and have to be covered by the patients themselves. In other words, every health insurance patient finances charlatanism. This is an unspeakably bad signal of current health policy. In addition, federal parties on the one hand advocate climate protection and scientific discourse, but on the other hand do not distance themselves from pseudo-medicine and charlatanry – on the contrary. This is particularly striking and absurd in the context of the pandemic: looking for scientific help and support in the fight against the pandemic, but at the same time offering a platform to miracle healers and conspirators. Here it must be said quite clearly that other countries, such as Great Britain, France, even Russia are clearly ahead of us in this respect. There, the state simply regulates this much more rigorously, which is also a good thing in this case. If politics does nothing or even does the wrong thing in this respect, then I am very glad that there are at least still private persons or associations like the INH that inform about these grievances.

INH: The pandemic has made it clear how difficult it is to communicate science to target groups. This extends so far that information is almost regarded as the opposite of what it is meant to be. Especially in the pandemic situation, there are many examples of this. In part, the media also encourage this, for example, by structuring press articles in such a way that the real “message” is not even clear from the headline.

In the medium term, do you see opportunities to improve both science communication – especially via the media – and the general public’s ability to perceive it? Would it be necessary to establish critical scientific thinking and the concept of science itself in school lessons?

Prof. Bräuer: Teaching science at an early age in school would indeed be a very good starting point. Let’s be honest, thinking for oneself is practically completely taken away from us nowadays, thanks to smartphones and other nice gimmicks. Almost everything happens digitally these days, which doesn’t only have advantages. People with a large media reach can spread information (regardless of whether it’s the right or wrong information) unfiltered and unhindered – that’s not necessarily a blessing.

At the moment, it seems that more effort has to be spent on damage limitation through so-called fact checks than on conveying actual facts and knowledge. Those who have not learned how to interpret scientific data or even how to read scientific publications clearly have to rely on others (in this case the media). But how can one rely on them when they themselves are part of the problem? An example: A talk show on public television invites two guests on the same topic. One of the two guests has been working, researching and publishing successfully on the topic of discussion for years – in other words, he is internationally recognised in his field; the other guest is also a scientist, but with a completely different expertise. How is the viewer (supposedly a layman in the field anyway) supposed to differentiate which of the two – let them be professors – is right? Quite simply, he can’t. If, however, he knew from his school days how science actually works and that there really is a currency for expertise, he would be very much helped here. After all, if you have a toothache, you trust your dentist and don’t go to a dermatologist.

Another big problem with the whole debate is emotion – all of us have experienced it ourselves during discussions with vaccination opponents or convinced homeopaths. Those who become emotional are no longer rational, and this prevents any further discourse. Unfortunately, the latter get emotional very quickly because they run out of arguments. Honestly? I think it will be a long and arduous road to improve science communication for the general public. Fortunately, the beginnings (podcasts, videos, educational campaigns, etc.) have already been made.

Finally, however, I would like to note that one should not always necessarily blame the patient for everything. Most of them seek and find refuge with a non-medical practitioner because of bad experiences with their family doctor or the “classical” medical practitioner – often because of the very limited “consultation time”. Of course, alternative practitioners take a lot of time, have an open ear, take a life history and in the end even prescribe an individually tailored sugar pellet that has no side effects – it couldn’t be better. Since many complaints are self-limiting anyway, the time factor is of course an additional plus point for the holistic approach. So we practically have it in our own hands.

We would like to thank Prof. Lars Bräuer very much for this interview. As a joint conclusion, we can certainly draw: There is still much, much to do in the field of education, health literacy and science communication. The INH remains “on it” – and people from the medical practice and medical science scene like Prof. Bräuer and his co-author Falk Stirkat are invaluable in this.

Picture credits: Gino Crescoli auf Pixabay

Book cover: G+U-Verlag / Sample photo: INH

4 Replies to “In the patient’s interest – An interview with Prof. Dr Lars Bräuer”

Comments are closed.