The second part of our series about the “homeopathic criticism on criticism on homeopathy” covers why critics conclude that there is no reliable evidence for the efficacy of homeopathy beyond placebo.

„There is not a single good quality trial showing homeopathy works“

This is how the UK-based Homeopathic Research Institute (HRI) cites their critics on their website “Homeopathy FAQs” [1]. The above statement is absolutely correct, though somewhat trivial: One single study never can “show” that “homeopathy” works. At best, if a trial is of good quality, it may give an indication that homeopathy might be more effective than placebo in the one medical condition that was tested in the trial, but not more. For reasons why this is the case, please refer to our previous article “Criticism on criticism on Homeopathy Pt.1: There is no evidence” [2].

“There is no reliable evidence that homeopathy is more effective than placebo in any clinical condition“

This is the correct, no longer trivial statement of the critics on homeopathy, for it can be falsified by presenting reliable evidence for efficacy in the case of a single clinical condition only. Though HRI does not explicitly refer to the proper wording, it is clear they want to argue against the notion of non-existing positive results. To identify examples of clinical conditions where homeopathy is shown as effective beyond placebo is a proper way in the attempt to contradict us critics, for the existence of just one such condition would prove the statement wrong.

Background: What is reliable evidence?

State-of-the-art evidence would include clinical trials designed as placebo-controlled double-blinded randomized clinical trials (RCT), which we explained comprehensively in part 1 of this series [2].

However, one single study alone cannot be reliable evidence. Evidence requires at least that a study has been replicated independently, i. e. repeated with other patients by another independent research team, which came to similar results. Since it is usually not easy to evaluate and pool different studies, a systematic review is required to build a solid conclusion, in which all available studies are considered, not just the most favorable ones.

To properly appreciate a study it is essential to consider its quality, which indicates how reliable it resembles reality. This is done by checking whether some essential criteria are met. Current procedure is to check for the “risk of bias” as set forth by the Cochrane Collaboration [3]. Eventually, a study is rated to be of “low”, “unclear” or “high” risk of bias from what could be expected in the real world. Naturally, a low risk would indicate a good quality study, a high risk of bias a poor one.

To determine this risk of bias, researchers refer to a list of criteria mainly to assess if the procedures for blinding and randomization were sufficient, and if the results of all the patients are reported completely. Authors must disclose these items in their report, otherwise the study is considered to be of unclear risk of bias, which indicates neither good nor bad quality.

It should be evident that reliable evidence can consist of low risk of bias studies only, where chances are good that the result is for real. If, for example, blinding of patients was insufficient, then patients in the placebo group, who now know they did not receive a possibly active treatment, might not attribute any positive development to the treatment and might not report it. On the other hand, patients who know of having received the (possibly) active drug, might be on a lookout for any positive development and might overrate its impact. Especially in studies on homeopathy, many of the data are assessed by asking for a patient’s subjective ratings of their experience, which renders it very important that the patient is “unbiased” in filling out the questionnaire or in answering the interviewers.

Not only insufficient blinding is likely to distort the outcome of a clinical study in favor of homeopathy. As evidence indicates, on average any shortcoming in quality does the same and yields more positive results [3, Chapter 8.5]

In a nutshell:

Reliable evidence consists of a number of independently replicated RCTs, a systematic review checking the quality of all the relevant studies in the field, and compiling a conclusion which resembles the best guess at what is to be expected in the real world.

HRI does quite acknowledge that more research is needed to replicate the available “promising” studies and that this has not yet been done sufficiently. But what does that mean for the question of existing evidence? Well, an independent replication may or may not yield similar results as before, which gives way to a somewhat unclear position: Homeopaths are certainly wrong assuming that future replications will surely corroborate the original findings, while critics cannot prove that successful replications are impossible. Consequently, the statement “there is no reliable evidence” is an absolutely correct scientific statement, not excluding that this could change in the future. This is in fact the strongest possible reservation against the evidence base in homeopathy, in accordance with todays sciences self-perception – which should not be misunderstood as assertion about that this might not happen in the future.

What good evidence is available?

However, the HRI points out positive studies on homeopathy for some clinical conditions, in order to refute the above statement of the critics. Here is a short overview:

(1) Individualized homeopathic treatment of childhood diarrhea

There is a review by Jacobs et al. where three studies with herself as lead author are considered [4]. All studies were performed under the same protocol. So, this is certainly not a summary of independent replications. Any shortcomings in study design or protocol or even handling might go unnoticed.

In the review of Jacobs, three studies are considered:

Jacobs (1993) with a small number of children in Nicaragua [5],

Jacobs (1994) with a larger number of children also in Nicaragua [6],

Jacobs (2000) with children in Nepal [7].

In the CORE-Hom database of the Carstens-Foundation [8] only one more study for the same clinical condition is listed (Cadena (1991)), but the record indicates that no statistical evaluation was included in that particular study. The three studies above thus completely reflects the available evidence for the homeopathic treatment of childhood diarrhea.

An assessment of the quality of these studies can be found in the systematic review on individualized homeopathy by Mathie et al. [9]: Only the paper from 1994 was rated “unclear risk of bias”, while the other two were rated as “high risk of bias”, that is, of poor quality.

Conclusion: Due to the poor quality of the available studies, there is no reliable evidence for a homeopathic treatment of childhood diarrhea. Note: There is a fourth paper on childhood diarrhea by the same author using non-individualized homeopathy, which could not show any advantage of homeopathy either.

(2) Individualized homeopathic treatment of otitis media in children

The HRI cites two works here:

Jacobs (2001) [10] In the review of Mathie (2014), this study is rated as of medium quality only [9]. In this preliminary study the results were not statistically significant, some minor advantages of homeopathy beyond placebo occurred but are likely to be attributed to random effects. In order to prove this effect, the authors wrote that a considerably larger study would be required (243 evaluated subjects, not only 72, as in this paper).

Sinha (2012) [11] According to the authors of this study, this was only a pilot study that was carried out without any blinding – which prevents it from being reliable. This study was not yet subject to quality assessment in any systematic review. But even on first glance the study looks very doubtful: The authors compared homeopathy to standard treatment, which, in this setting in India, consisted in 95 % of the cases of the use of antibiotics, which most authors consider useless as the condition is mostly caused by viral infection. Also, they looked at a condition which according to German guidelines remits in 78% of the cases within two to seven days. This corresponds very poorly with the study’s timeline of observations at 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after diagnosis, whereby the first three days remained without intervention – which renders the only statistically significant result occurring at day three meaningless.

A review performed by the Australian Ministry of Health lists another study, Harrison (1999), which was judged to be of poor quality only [21].

The CORE-Hom database lists another PCT [8]. In this work by Mössinger (1985) the data of 38 children were analyzed. According to the database, no significant advantage beyond placebo was achieved.

Conclusion: There is not a single high-quality study here that would have produced a reliable positive result.

(3) Use of the homeopathic remedy Galphimia glauca against hay fever

Here the HRI refers to a work by Wiesenauer (1996), which represents a systematic review of essentially his own work on this subject [13]. He comes to a positive conclusion, not shared by other authors:

Linde (1997) investigates four works by Wiesenauer [14], which pooled together show a positive effect (odds ratio 2.03 in favor of homeopathy), although Linde concludes that he has found no indication for which there is sufficient evidence that homeopathy is effective beyond placebo. Obviously, this statement is not based on the figures alone but allows for the questionable quality of the studies.

Mathie in his systematic review of non-individualized homeopathy found insufficient quality in three of Wiesenauer’s studies (1 medium, 2 poor) and has included two other works in his meta-analysis of hay fever (”allergic rhinitis“) [15]. He also concludes that there is a lack of reliable evidence for the efficacy of homeopathy for any clinical condition.

The review by the Australian Ministry of Health comes to the same conclusion.

Conclusion: In contrast to the author of the one review cited by HRI, all other reviews agree that there is no reliable evidence. Since the lead author of the studies himself is probably more prone to be biased in favor of his results, the negative assessment from the other three reviews appears more solid.

(4) Use of pollen C30 as an isopathic remedy against hay fever

HRI cites a study by Reilly (1986) [16], which is indeed considered by most reviewers to be of high quality – except for Mathie (2017). He considers this paper of poor quality due to unclear reporting of the blinding and incomplete reporting of results [15].

Even if we admitted that this study was rated as good quality by most reviewers and yielded a positive result, there is still no replication of this promising work for homeopathy – for more than 30 years now. Why this is the case is open to speculation: it is impossible to judge whether an attempt to replicate the positive result has failed or not.

(5) Use of the homeopathic remedy Oscillococcinum for the treatment of influenza

The HRI indicates a study in which Oscillococcinum is supposed to be effective against influenza. This work by Mathie (2012) is a Cochrane review, i. e. a systematic review carried out according to strict rules [17] and, if the statement of the HRI would apply, should actually be counted as reliable evidence.

First of all, it was not influenza that was treated, but influenza-like infections, i. e. common colds. Then Mathie, who works for the Homeopathy Research Institute himself and for sure is not an opponent of homeopathy, comes to the conclusion:

“There is not enough evidence to draw solid conclusions about Oscillococcinum for the prevention or treatment of influenza or flu-related infections. Our results do not exclude the possibility that Oscillococcinum may have a useful clinical effect, because of the low quality of the studies in question, the evidence is not convincing.“

Well, a reliable proof of thoroughly positive effects looks different.

(6) Use of the homeopathic complex remedy Vertigoheel against vertigo

The paper by Schneider et al. is a review of four papers that examined the remedy Vertigoheel for the treatment of vertigo in comparison to other therapies [18]. Only two of the papers (Weiser 1998 [19] and Issing 2004 [20]) were randomized controlled studies. Unfortunately, these works are not included in Mathie’s reviews. In the review of the NHMRC, the work of Issing is rated at medium to high risk of bias, while the work of Weiser is rated at medium risk [21].

In all four papers, it was found that the results obtained with Vertigoheel did not differ from the conventional therapies – although this is only meaningful if these conventional treatments are effective beyond placebo themselves and have been applied properly.

If Vertigoheel actually was effective, however, this is a point more against the teaching of homeopathy than in favor. The prescription was not based on an individual assessment of similarity between symptoms and the drug’s “remedy-picture”, which should be established in a detailed first session. Instead it was based on the not very specific diagnosis of ”dizziness“, which can have a large variety of different causes. Secondly, Vertigoheel is a complex remedy of four different homeopathic remedies, which, according to homeopathic teachings, at least makes it very difficult to achieve healing. It should be noted that Heel’s complex remedies are not considered to be homoeopathic drugs, but should act in accordance with homotoxicology, a doctrine of salvation based on the alleged detoxification of the body and not on influencing the alleged vital force as in homeopathy [22].

Conclusion: Once again there is no reliable evidence of homeopathy as an effective treatment for this condition. Based on the quality of the relevant studies, the results should not be considered as valid. But if homeopaths insist on their validity, then the studies rather indicate that the foundations of homeopathy are wrong.

In summary

At best, there is only a single good study that showed some benefit of homeopathy – Reilly – amongst all the examples given by the HRI. It is unclear how many clinical conditions were considered in PCTs of homeopathy, as many different figures are given: The UK-based Faculty of Homeopathy says 61 conditions, 85 conditions were considered in the review by the Australian Ministry of Health, and the German CORE-Hom database lists more than 50 indications under the letter “A” alone. With the standard risk of an Type I error (false positive result) of 5%, it is to be expected that there are a few studies that are of good quality and in favor of homeopathy. In this respect, Reilly’s study seems more the exception proving the rule (which is further mitigated by the fact that this work has not been reproduced for decades – or has been reproduced with a negative result, but this never came to be published – we don’t know that).

Clinical relevance

It is well known that homeopathy raises strong claims of its efficacy:

“A carefully selected homeopathic medicine can relieve quickly, safely, gently and without side-effects the symptoms of severe, acute and chronic complaints, such as migraine, neurodermitis, bronchial asthma, colitis, rheumatism and many other diseases. This also applies to acute conditions of a bacterial or viral origin.” [23]

This is what the president of the German Central Association of Homeopathic Doctors, essentially the highest German homeopath, writes on her practice homepage. Thus the patient who decides in favor of homeopathic therapy can expect that their state of health will improve substantially more and/or faster than if they hadn’t done anything at all. Therefore, studies of homeopathy should not only result in a statistically significant benefit beyond placebo; this would only mean that the effect is just strong enough to be recognized in sophisticated statistical analysis and might be of no practical benefit. But it should also be clinically relevant, i. e. show a noticeable and substantial improvement for the patient.

The clinical relevance in a study results from two aspects: On one hand, if the study authors have chosen a characteristic as main outcome measure that meets the expectations of the patient well enough for them to judge the treatment as a success or not. On the other hand, however, the difference must also be substantial, so the benefit should be of a magnitude the patient can really experience. Irrespective of the quality of the studies cited by the HRI – i. e. their credibility – here is a short look into what their results indicate regarding clinical relevance:

Childhood diarrhea:

Jacobs chooses the number of unformed stools on the third day of treatment. At this point in time, this figure has decreased significantly in both study groups, from an average of 7.7 events per day to 3.1 in the control group and to 2.1 under homeopathic treatment. This advantage of only one event per day disappeared completely on day 4:2.0 events in the homeopathic group, 2.1 under placebo, i. e. hardly distinguishable. By the way: the third day is the only day with a significant result. The difference of one event on day three alone certainly is some relief for the family – but is it a substantial improvement over placebo?

Otitis media:

Jacobs‘ placebo-controlled study did not even yield a significant benefit, so there is no need to worry about clinical relevance.

Galphimia glauca in hay fever:

Two weeks after the start of treatment, 34 (of 41) patients in the homeopathy group were free of symptoms or experienced significant relief, in the control group it was 21 (of 45) patients. After four weeks, 30 (of only remaining 37) patients in the homeopathy group were free of symptoms or had a significant improvement. In the control group, it was 20 (of only 35) patients [24]. Further out, only relative figures from other works are available, which do not permit an assessment of relevance.

Whether this will show a substantial effect remains to be seen.

Pollen C30 against hay fever:

In Reilly’s work, the severity of hay fever symptoms was determined by the patients themselves ever day, given on a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 100 (0 = no symptoms at all, 100 = extremely bad). At the beginning, the mean value in both groups was about 45, but with a big variance. The same showed in the changes: In the homeopathy group, scores ranged from an improvement by 80 points to a deterioration by 50 points. Practically the same thing happened in the control group: The range was from an improvement by 80 points to a deterioration by 60 points. If the patients had compared their results, they would not have been able to identify individual patients whose results were so good or so bad as to clearly identify them to be of the homeopathy or control group. The higher mean improvement of 17.1 points in homeopathy compared to only 2.1 points in the control group is a difference that no patient can actually perceive.

Oscillococcinum for influenza:

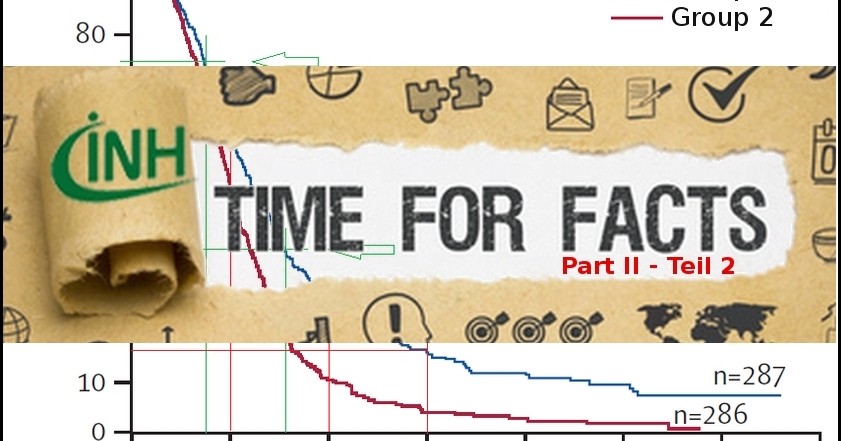

In the two works by Ferley [25] and Papp [26] the success of the therapy is judged by the recovery rate on the second day after start of treatment. In fact, there is a statistically significant advantage of the homeopathy group – which is only present on this very day, neither the day before nor the day after. This is illustrated in the graphic, which also shows how „radical“ homeopathy has been.

In the two works by Ferley [25] and Papp [26] the success of the therapy is judged by the recovery rate on the second day after start of treatment. In fact, there is a statistically significant advantage of the homeopathy group – which is only present on this very day, neither the day before nor the day after. This is illustrated in the graphic, which also shows how „radical“ homeopathy has been.

The graph shows the results of Ferley’s work [25], which were converted to even numbers of participants in both groups. From day 1 to day 2, the homeopathy group has achieved a small advantage indeed, but the parallel curves show otherwise that the recovery rates are practically the same.

The average duration of the illness was reduced only by about 6 hours, which should be meaningless, especially at night, if they happen while the patient is asleep. This is certainly not the therapeutic success that patients would want to achieve.

Vertigoheel against dizziness:

No comparison with placebo possible, as the drug was not compared with placebo but with other therapies.

In summary:

Even if one ignores the lack of credibility of the studies and takes a look at the results alone, the assertion that homeopathy can quickly achieve a drastic improvement of the patient’s situation is by no means apparent in the studies quoted by the HRI. At best, there is one potential use, Galphimia glauca in hay fever, but this would still have to be verified on the basis of independent study replications.

Quintessence

The works presented by the HRI as ”good studies“do not satisfy this claim – by far. Studies have been judged to be of inadequate quality in existing reviews of homeopathy. At best, there could be just one indication where a good study shows a positive result. This promising work on isopathy in hay fever has not been replicated for thirty years now, however. In addition, for statistical reasons, it is to be expected that even good studies will occasionally yield positive results, due to the risk of a Type I error (probability for false-positive results).

The clinical effects, on the other hand, are relatively minor and in no way support the claim of homeopathy to be a thoroughly effective therapy, helping patients to a substantial degree.

The HRI’s arguments against ”There is not a single good quality trial showing homeopathy works“ is thus not supported by evidence.

Acknowledgement:

This article is published here with kind permission of the author, Dr. Norbert Aust. The author would like to thank Udo Endruscheit and Sven Rudloff for their help with this English version of his original blog-article: http://www.beweisaufnahme-homoeopathie.de/?p=3312

References

[1] NN.: „There isn’t a single good quality trial showing homeopathy works“, webpage of the Homeopathy Research Institute, checked 01.12.2017, Link

[2] Aust, N: Criticism on criticism on Homeopathy Pt. 1: There is no evidence, blog-article (Link) and INH website (Link)

[3] Higgins JPT, Green S.: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; The Cochrane Library, 2008. Link

(Chapter 8: Asessing Risk of Bias)

[4] Jacobs J, Jonas WB, Jiminez-Perez M et al.: “Homeopathy for childhood diarrhea: combined results and metaanalysis from three randomized, controlled clinical trials“, Pediatr Infect Dis J (2000);22:228-234 Link

[5] Jacobs J, Jiminez LM, Gloyd S et al.:“Homoeopathic treatment of acute childhood diarrhea – a randomized clinical trial in Nicarague“,British Homeopathic Journal (1993);82:83-86

[6] Jacobs J, Jiminez LM, Gloyd SS et al.: “Treatment of Acute Childhood Diarrhea with Homeopathic Medicine: A Randomized Trial in Nicaragua“, Pediatrics(1994);93(5):719-725 Link

[7] Jacobs J, Jiminez M, Mathouse S et al.: “Homeopathic Treatment of Acute Childhood Diarrhea: Results from a Clinical Trial in Nepal“, Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine(2000);6(2):131-139 Link

[8] NN: “CORE-Hom database, A database on Clinical Outcome Research in Homeopathy“, database of the Carstens-Foundation, free access requires registration , Link

[9] Mathie RT, Lloyd SM, Legg LA et al.: “Randomised placebo-controlled trials of individualised homeopathic treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis“, Systematic Reviews 2014;3:142, Link

[10] Jacobs J, Springer DA, Crothers D: “Homeopathic treatment of acute otitis media in children: a preliminary randomized placebo-controlled trial“, Pediatr Infect Dis J (2001);20(2):177-83 Link

[11] Sinha MN, Siddiqui VA, Nayak C et al.: “Randomized controlled pilot study to cpmpare Homeopathy and Conventional therapy in Acute Otitis Media“, Homeopathy (2012);101:5-12, Link

[12] NN: DEGAM-Leitlinie Nr. 7: Leitlinie „Ohrenschmerzen“, aktualisierte Fassung 2014, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin, AWMF-Registernummer 053/009 Link (in German)

[13] Wiesenauer M, Lüdtke R:“A Meta-Analysis of the Homeopathic treatment of Pollinosis with Galphimia Glauca“, Forschende Komplementärmedizin (1996);3:230-234, Link

[14] Linde K, Clausius N, Ramirez G et al.: “Are the clinical effects of homeopathy placebo effects? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials“, The Lancet (1997);350:834-843 Link

[15] Mathie RT, Ramparsad N, Legg LA et al.: “Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of non-individualised homeopathic treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis“, Systematic Reviews 2017;6:663 Link

[16] Reilly TR, Taylor MA, McSharry C et al.: “Is homeopathy a placebo response? Controlled trial of homoeopathic potency, with pollen in hayfever as model“, The Lancet (1986) 328:8512:811-816 Link

[17] Mathie RT, Frye J, Fisher P:“Homeopathic Oscillococcinum (R) for preventing an treating influenza and influenzy-like illness (Review)“, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012 Issue 12 Art.No.: CD001957 Link

[18] Schneider B, Klein P, Weiser M: “Treatment of Vertigo with a Homeopathic Complex Remedy Compared with Usual treatments“, Arnzneim.-Forsch./Drug Res.(2005);55(1):23-29 Link

[19] Weiser M, Strösser W, Klein P: “Homeopathic vs. Conventional Treatment of Vertigo: A Randomized Double-blind Controlled Clinical Study“, Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (1998);124(8):879-995 Link

[20] Issing W, Klein P, Weiser M: “The Homeopathic Preparation Vertigoheel(R) Versus Gingko biloba in the Treatment of Vertigo in an Elderly Population: A Double-Blinded, Randomized, Controlled Trial“, J. Altern. Complement. Med. (2005);11(1):155-160 Link

[21] National Health and Medical Research Council. 2015. “NHMRC Information Paper: Evidence on the effectiveness of homeopathy for treating health conditions “, Canberra: NHMRC;2015 Link

[22] NN: Homotoxikologie, article in Homöopedia.eu (in German) Link

[23] Entry „Homöopathie“ on the website of C. Bajic Link – checked 25.11.2017 (in German)

[24] Wiesenauer M, Häussler S, Gaus W: “Pollinosis-Therapie mit Galphimia Glauca”, Fortschr. Med (1983);101(17): 811-814 Link

[25] Ferley JP, Tmirou D, D’Adhemar D et al.: “Evaluation of a Homeopathic Preparation in the Treatment of Influenza-Like Syndromes“, Br. J. clin Pharmac. (1989);27:329-335 Link

[26] Papp R, Schuback G, Beck E, et al.: “Oscillococcinum(R) in patients with influenzy-like syndromes: A placebo-controlled double-blind evaluation“, British Homeopathic Journal (1998);87(2):69-76 Link

Picture credits: Fotolia_130625327_XS